Knee osteoarthritis

What is Knee osteoarthritis?

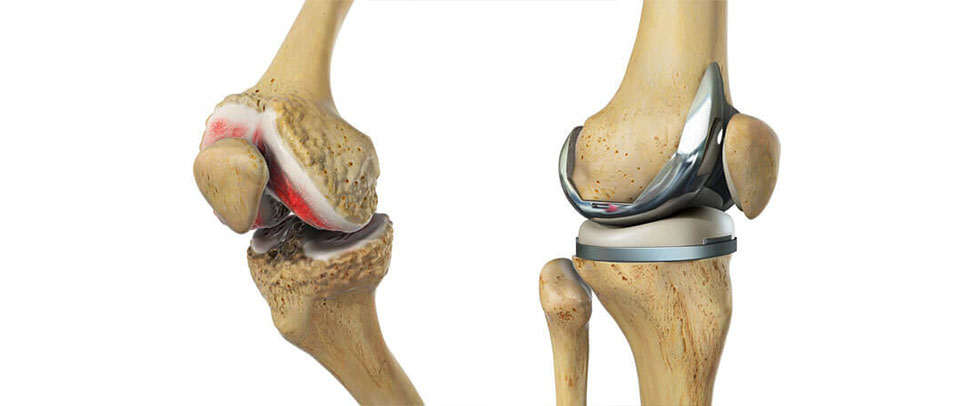

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common causes of knee pain. It is the progressive degeneration of the articular cartilage that coats the ends of the 3 bones in the knee (thighbone, shinbone and kneecap) and which cushions the knee, preventing damage to the bone and allowing smooth movement. In advanced cases, the cartilage wears away until the bone is left bare and becomes diseased, and sometimes deformed. These deformities are called osteophytes, or bone spurs. The synovial membrane is chronically inflamed and produces an excessive amount of fluid, which makes the joint swollen. The articular capsule (see Glossary) becomes taut and limits the range of movements.

OA predominantly affects patients over 60, and it is more common in women than men.

It can be divided roughly into 2 types: primitive which is not due to any specific cause, or secondary which is a result of some other pathology.

With the development of new technologies in various fields (bio-technologies based on physical stimulation, medication, surgical) you can now expect to regain a good quality of life.

What causes it?

It can be caused by a wide variety of things: excessive strain on the joint (perhaps during sport or manual work, or being overweight), congenital deformities (such as knock knees or bowlegs), past knee injuries or fractures, infections, rheumatoid diseases, hereditary causes, a hormonal imbalance or just wear and tear over the course of your life.

How does it feel?

Initially, you may feel stiffness and pain in your knee – particularly when standing or walking – and you may have difficulty bending or straightening your leg. The knee may sometimes feel hot to the touch and may swell. It is also common for the symptoms to come and go. As the disease progresses, even normal activities, such as sitting down or climbing stairs, will become painful and your knee may seem to be enlarged and/or irregular in shape.

Diagnosis

An X-ray of the knee (if possible weight-bearing, i.e. standing up) should be enough to diagnose osteoarthritis: the space between the femur and tibia, or patella and femur, will be narrowed, and in advanced cases the bones will be deformed. Your doctor will also examine your knee and consider your case history.

Treatment – conservative

Your doctor may prescribe any, or all, of the following treatments:

- Change of lifestyle – for example losing weight, and regulating your level of activity

- Medication – chondro-protective (e.g. glucosamine, chondratin sulphate, or methyl methanesulfurnate), or anti-inflammatory medication

- Injection therapies such as hyaluronic acid or cortisone injections

- Electrical stimulation therapies, shock wave therapy. and magnetotherapy

- Physiotherapy – exercises to regain the range of movement of your leg, your balance, and to rebuild the muscles.

Treatment – surgical

In many cases, the surgical treatment of osteoarthritis is similar to the treatment for cartilage defects although your surgeon will remove any bone spurs (so-called osteophytes) and realign the limb if it is deformed.

1. Arthroscopic Debridement: this is carried out on more minor damaged areas and is aimed at preventing or delaying further progression of the problem. This procedure is usually used when the lesion is too large for a grafting type procedure or the patient is older and an artificial knee is planned for the future. The surgeon cleans up the joint, trimming any rough edges of cartilage, and removing loose particles. This procedure is sometimes referred to as chondroplasty. It is only intended to be a short-term solution, but it is often successful in relieving symptoms for a few years.

2. Bone Marrow Stimulation Procedures: abrasion arthroplasty and arthroscopic microfracture are two procedures that are performed to stimulate the bone marrow, making it form scar tissue or ‘fibrocartilage’, which replaces the damaged articular cartilage.

- Abrasion Arthroplasty: When the cartilage has worn away and bone rubs on bone, the bone-surface becomes hard and shiny. During arthroscopy, the surgeon can use a special instrument known as a burr to scrape off the hard, polished bone tissue from the surface of the joint. The scraping action causes a healing response in the bone, with new blood vessels entering the area, bringing stem cells, and causing the formation of fibrocartilage. The fibrocartilage that forms may not remove all the symptoms of pain in the knee, and therefore this may be only a temporary solution.

- Arthroscopic Microfracture: The surgeon will clear away the damaged cartilage, and then use a blunt tool to poke a few tiny holes in the bone under the cartilage. Like abrasion arthroplasty this procedure is used to get the layer of bone under the cartilage to produce a healing response, triggering the formation of new cartilage (mainly fibrocartilage) inside the lesion.

3. Partial/Total Knee Replacement: The surgeon will make an incision in the front of the knee of 4 to 9 inches long. Then he will remove the minimum amount of damaged bone from the joint surfaces (thighbone and shinbone), and he will replace it with a synthetic cap on the thighbone and a matching part on the shinbone. If the patella has also been affected by the arthritis, the surgeon will again remove the damaged bone and replace it with a synthetic button. He will then align the joint and ensure that the knee bends and straightens correctly. After surgery, you should have a correctly aligned leg and a full range of motion.

In some patients the arthritis may have affected only a part of the joint, and so much less bone is removed. A smaller “half” cap is applied to the thighbone, and a small plate is attached to the shinbone, with a small piece of plastic in between. You will normally have to stay in hospital between 3 to 10 days, depending on your personal rate of recovery, and also on how difficult it will be to manage at home (stairs, assistance at home etc.).

In order to increase the life of your new knee you must maintain an appropriate weight for your height, develop good muscle tone and avoid activities that will put strain on the knee joint.

Revisions

In the unlikely event that there are problems with your knee replacement (pain in the knee joint, swelling, reduced movement, or if you hear an unusual “clicking” noise) you should book a visit with your doctor who will examine you, prescribe new X-rays, a blood test, and in some cases, a bone scan. He will then decide if you need a so-called “revision” i.e. the replacement of some or all of the components with new ones. Problems with the knee replacement are normally due to an infection, overuse or injury – however, it is worth underlining that this happens only rarely. Revision surgery should be performed by an experienced surgeon. Results are satisfactory although often not so good as after a primary implant.

Rehabilitation after surgery

Debridement: Your surgeon will instruct you to place a comfortable amount of weight on your operated leg using crutches, and to increase the weight on your operated leg until you can walk normally.

Bone marrow stimulation procedures: If the operation is performed on a weight-bearing part of the knee, you will have to use crutches for at least 8-12 weeks to allow the new cartilage to develop properly. If the operation is on the back of the kneecap or the adjoining bone, you will be able to walk normally but will have to avoid putting any pressure through a bent knee (i.e. going up and down stairs, walking on steep slopes, squatting etc) for 6-8 weeks. Activity should be gradually increased after that, rebuilding the muscles gradually, under the supervision of a physiotherapist.

Partial/Total Knee Arthroplasty: You will be able to walk almost immediately after the operation, although your doctor will prescribe crutches to help with balance and to make walking more comfortable, and he will give you light exercises to start rebuilding your quadriceps muscles. A physiotherapist will teach you how to get out of bed correctly, how to walk with crutches, and how to dose your weight according to the level of discomfort you feel. Most patients keep their crutches for about a month. The physiotherapy will become more strenuous as time passes in order to rebuild your muscles, and particular attention will be given to straightening the leg fully. You will need to go back to your surgeon at regular intervals for checkups, bringing a recent X-ray with you.

When will I be back to normal?

Debridement: Return to normal activity will depend on how much discomfort and swelling you experience. These are not usually severe and, if you were quite fit before surgery, you could be back to normal in a few weeks, and driving within 4-5 days of the operation.

Bone marrow stimulation procedures: It could be 9-12 weeks before everyday activities become completely comfortable, although you can start driving after 15 days. The damaged area goes on developing for months after surgery, so certain sports may not be advisable for at least 3 months.

Total Knee Replacement: Most patients return to work after about 2 months, although those who have a sedentary job may be able to return quicker than this. Everyone is different and your doctor will be able to advise when your muscles are strong enough for you to return to work. You can start driving when the wound is healed and you have good control of the leg (after 2-4 weeks).

Partial Knee Replacement: Many patients go back to work after about 4-5 weeks, although depending on how physically demanding your job is, you may be able to return earlier, or likewise have to wait a little longer before going back. Driving should be possible when the wound is healed (after 2 weeks).

Ideally, after knee replacement, patients will be able to resume their previous lifestyle activities. Some patients may need to modify their choice of activity in order to prolong the life of their prosthesis. Similarly, it is very important to maintain a correct bodyweight to avoid undue stresses on the implant.